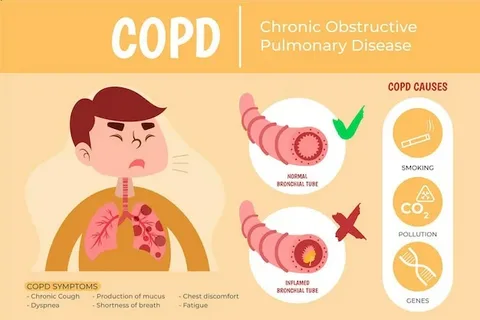

It often begins with a cough that never goes away. Then come the missed steps, the fatigue, the breathlessness while tying a shoe or walking from one room to another. For millions of Americans living with chronic lung diseases like COPD, daily life becomes a constant calculation: How far can I go without needing to rest? Is this just a bad day, or is something getting worse?

When hospital visits turn frequent and symptoms escalate, many families make a decision they never thought they’d face—managing a chronic respiratory illness entirely at home.

It’s a decision filled with unknowns. What does good care at home actually look like? Which tools help, and which only create more clutter? What do people get wrong about oxygen, nebulizers, and breathing exercises? And perhaps most importantly: how do you manage a disease that doesn’t go away?

Why Home Isn’t Always Easier

There’s a common belief that patients with COPD or other lung diseases recover better in the comfort of their own homes. But “comfort” is a relative term when the air feels thinner by the hour. The home environment can, in some cases, make things worse—especially when it’s filled with triggers like dust, pet dander, mold, or poor ventilation.

That’s why professional assessments are crucial. People often assume that if a patient can breathe comfortably in the living room, they’ll be fine everywhere else. But the reality is more complicated. Temperature fluctuations between rooms, the presence of carpets, cooking fumes, or even scented candles can silently increase the effort it takes to breathe.

The first thing many pulmonary therapists do is not adjust medication—but adjust the room. Moving furniture to allow easier movement with oxygen tanks, swapping out fabric curtains for hypoallergenic options, and reducing clutter can have a measurable effect on lung stress.

Without this kind of intervention, home becomes a place of risk rather than recovery.

The Oxygen Question: More Isn’t Always Better

Supplemental oxygen seems like a simple fix: low blood oxygen levels mean you need more oxygen, right? Not always. Too much oxygen can actually suppress the respiratory drive in certain COPD patients, especially those with chronic CO₂ retention.

This nuance is often lost in families trying to help. It’s not uncommon for someone to turn up the oxygen dial out of fear, thinking they’re doing the right thing. But oxygen therapy requires precision. Flow rates, humidification, delivery methods—all need to be tailored by respiratory professionals.

Equally important is ensuring that patients don’t become sedentary simply because they’re tethered to a tank. Movement—even slow, steady walking—can help clear mucus, improve circulation, and reduce feelings of anxiety that often accompany breathlessness.

It’s a delicate balance. But those who manage it often report fewer ER visits and a stronger sense of independence.

What Actually Helps (and What Doesn’t)

It’s easy to get overwhelmed by products and promises. A quick search online reveals devices claiming to “boost lung power,” herbal remedies, and exercises that promise miraculous improvements.

But when you speak to pulmonologists and respiratory therapists, the message is much simpler: consistency works better than novelty.

- Pursed-lip breathing helps maintain open airways and improve oxygen exchange.

- Inspiratory muscle training—using a small handheld resistance device—can increase lung strength.

- Daily airway clearance techniques, like huff coughing or postural drainage, reduce the risk of infection.

- Scheduled rest periods paired with short movement intervals are often more sustainable than long bouts of inactivity.

What doesn’t help? Ignoring nutrition, neglecting hydration, and isolating. Malnutrition is a silent threat for COPD patients, especially those who find eating exhausting. Dehydration thickens mucus, making it harder to clear airways. And isolation can lead to depression, which further reduces activity—and therefore lung capacity.

That’s why truly effective home care focuses not just on breathing, but on everything that influences it: food, movement, emotion, and environment.

The Psychological Toll of Struggling to Breathe

Living with a chronic lung condition is more than a physical challenge—it’s a psychological one. Many patients report panic attacks triggered not by emotion, but by the terrifying sensation of being unable to draw a full breath.

These episodes can spiral quickly. The fear of breathlessness leads to inactivity. Inactivity weakens the lungs. Weaker lungs make breathing harder. And the cycle continues.

Families and caregivers are often unprepared for this emotional loop. What seems like stubbornness may actually be anxiety. What looks like laziness could be fatigue layered with fear.

This is where structured, empathetic care becomes crucial. Professionals trained in pulmonary support know how to interrupt this cycle—not with pressure, but with pacing, reassurance, and expertise. Providers such as care mountain home healthcare are known not only for clinical skills, but for restoring a sense of safety to the daily lives of those who live with these invisible fears.

What Families Wish They Knew Sooner

One of the hardest parts of managing lung disease at home is knowing when something small is actually serious. A subtle change in energy, appetite, or cough can signal the start of an exacerbation—often days before oxygen levels drop.

Families often say, “We didn’t think it was bad enough yet.” But in chronic respiratory illness, early action is everything. That means keeping logs, tracking weight changes, and knowing when to call in help.

One can receive guidance from professionals like those at care mountain in Denton, who understand what to watch for and when to escalate care. They help families create action plans—not just for emergencies, but for everyday stability.

These plans often include backup medications, portable nebulizers, and environmental checklists. But they also include something harder to define: the confidence to act without panicking.

When breathing becomes effort, every decision matters. Every piece of furniture, every missed meal, every unspoken symptom can tip the balance between control and crisis. Managing chronic lung disease at home is not just about staying out of the hospital. It’s about creating a way of life that respects the body’s limits while still preserving its dignity.

And when that balance is found—through knowledge, patience, and the right kind of support—home becomes not just a place to live, but a place to breathe easier.